Miceli, Sergio

(ed. and transl. by Marco Alunno)

6.0. Theater and Cinema Musicals. The end of Happy End

The reason why I will speak here, with regard to Les Misérables, about only two theater and cinema musicals among several hundreds of well-known and admired titles will become clear, I hope, in the rest of this work.65 At any rate, I can briefly anticipate it hereafter. The two musicals are: West Side Story (1957) and Man of La Mancha (1965). The fact that they (including Les Misérables) have a tragic and bitter end where the protagonist dies is important because — it is worth remembering it — in a musical the Happy End is usually mandatory. In addition to this, all of them have a ‘classic’ background in common: Shakespeare for West Side Story, Cervantes for Man of La Mancha and Hugo for Les Misérables.

65 I will recall here that musicals have been of my special interest in several occasions: Sergio Miceli, “Tipologie filmico-musicali. Il Musical americano (I),” in Musica/Realtà, XXV, n. 75 (2004): 19-47; id., “Tipologie filmico-musicali. Il Musical americano (Il),” ibid., XXVI, n. 76 (2005): 23-51; two two-years courses at the Florence and Rome “La Sapienza” University (2004-2005 and 2005-2006); and the participation in the international conference From Stage to Screen, Musical Films in Europe and United States (1927-1961), chairmen Raymond Knapp and Sergio Miceli, proceedings edited by Massimiliano Sala (Turnhout: Brepols, 2012). I also dedicated some chapters of my Film Music: History, Aesthetic-Analysis, Typologies to this subject. All this means that the list of recordings that will follow is just a selection of what is actually available on the market.

Another common element of some interest to the scope of the present work is that several pop and lyric singers (from Plácido Domingo to Elvis Presley) added one or two of the most famous songs from each musical in their repertoire. Moreover, they have been internationally successful, Cats (1981) and The Phantom of the Opera (1986) by Andrew Lloyd Webber being the only ones that could compete with them. The only negative exception has been the film version of Man of La Mancha that, since its release, has not encountered the critics’ benevolence and the audience’s reaction has turned out to be quite tepid despite the featured celebrities (Peter O’Toole and Sophia Loren). Finally, let us compare the release date of Les Misérables with those of West Side Story (1961) and Man of La Mancha (1965). Les Misérables was premiered in Paris in 1980, but a different version in English that premiered in 1985, is considered to be the true beginning of this musical’s long and successful life. The above mentioned common elements and the fact that that West Side Story and Man of La Mancha were born in the same span of time is not enough to make them similar to each other. For example, lighting and set design in Man of La Mancha seem always shabby and approximated. West Side Story, instead, is a sui generis musical because it represents a break with tradition. In fact, many consider it the musical that marked the beginning of that break. Moreover, besides Man of La Mancha’s libretto being more suitable for a European’s than a US’ audience, its authors seem to be drifting toward the tradition and paying structurally, but not musically attention to Kurt Weill. Said otherwise, in Man of La Mancha, there is something that recalls a Singspiel and the simplicity of the most famous melodies — Impossible Dream, Dulcinea, etc. — explains why a viewer might get attached to them in a visceral way. Instead, West Side Story has a more varied audience that includes also exigent spectators. Although both musicals are ‘classics’ that shaped history, perhaps the first place pertains to West Side Story because of the great success obtained by its film version, whereas the film version of Man of La Mancha, as it has already been said, was a flop (certainly, Peter O’Toole’s dull interpretation did not help).

A lyric version of both musicals exists: one for West Side Story (with José Carreras and Kiri Te Kanawa, Studio Cast Recording), and two for Man of La Mancha, with a Spanish cast (Plácido Domingo and Julia Migenes in 1990, Studio Cast Recording), and in the French adaptation by Jacques Brel (with José Van Dam and Alexise Yema at La Monnaie theater in Bruxelles). Cervantes’ character is not new to Van Dam; in fact he interpreted him also in 2010, again at La Monnaie, in Jules Massenet’s comédie héroïque Don Quichotte (1910). And the story of Don Quijote is not new to the music literature; in fact Maurice Ravel, as one of the composers of Wilhelm Pabst’s Don Quixote (1933), wrote for that film the Trois Chansons (Don Quichotte à Dulcinée on texts by Paul Morand). However, instead of Ravel’s music, Pabst chose Jacques Ibert’s Quatre Chansons on texts by Pierre de Ronsard (Chanson du départ) and Alexandre Arnoux (Chanson à Dulcinée; Chanson du duc; Chanson de la mort de Don Quichotte).66 In that occasion, Ibert’s songs were interpreted by the famous bass Fëdor Šaljapin (Фёдор Шаляпин, first interpreter of Massenet’s Don Quichotte) and soon entered the repertoire of many bass and baritone singers.

66 After the cab’s accident that probably caused Ravel’s death four years later, the composer postponed many times the orchestration of his Trois chansons. Many biographers wondered why in Ravel’s last composition there is a clear return to tradition. No one could answer, but it was sufficient to think of the purpose of that music: Ravel was aware that film music, according to tradition, must be closer to the XIX than the XX century.

When comparing both versions of Man of La Mancha, the French one with José Van Dam and the adaptation made by the memorable author of many Parisian chansons like Ne me quitte pas (but Jacques Brel was Belgian) is undoubtedly the best. In fact, Van Dam interpreted L’Homme de la Mancha with such a passion that he left a lasting memory of it in European culture. But there are many other interpretations of the most famous songs of both Man of La Mancha and West Side Story, although there are also some obvious differences between the two. Such differences are mainly due to the fact that West Side Story has certainly more attractive songs than Man of La Mancha. Its songs are also much more agitated, rhythmically/harmonically irregular and with quite deep roots in jazz. This contrasts with those kinds of elementary rhythms (like in the waltz I Feel Pretty) that, among other things, offered Leonard Bernstein the possibility to balance those parts of the musical whose musical language was more ‘cultured’. Among many things Bernstein left to posterity, there is a book that deserves to be reflected upon. In the chapter American Musical Commedy, Bernstein makes a short historical review and states “[…] that the American musical theater has come a long way, borrowing this from opera, that from revue, the other from operetta, something else from vaudeville — and mixing all the elements into something quite new, but something which has been steadily moving in the direction of opera.”67 Then, in the next page he writes:

We are in a historical position now similar to that of the popular musical theater in Germany just before Mozart came along. In 1750, the big attraction was what they called the Singspiel, which was the Annie Get Your Gun of its day, star comic at all. This popular form took the leap to a work of art through the genius of Mozart. After all, The Magic Flute is a Singspiel; only it’s by Mozart.

We are in the same position; all we need is for our Mozart to come along. If and when he does, we surely won’t get any Magic Flute; what we’ll get will be a new form, and perhaps “opera” will be the wrong word for it. And this event can happen any second. It’s almost as though it is our moment in history, as if there is a historical necessity that gives us such a wealth of creative talent at this precise time.68

67 Leonard Bernstein, The Joy of Music (Pompton Plains, NJ: Amadeus Press, 2004), 190.

68Ibid., 191.

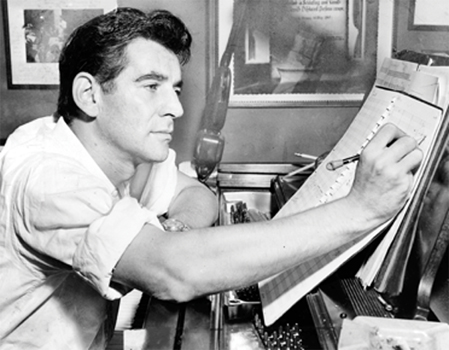

Precisely while writing this, Bernstein was about to complete West Side Story whose premiere occurred one year later: I convincingly think that those words were more than prophetic and certainly referred to his own work. It was a sort of self-investiture that made Bernstein happily proud of himself, although the comparison with Mozart would be quite audacious for anyone. On the other hand, West Side Story did not sound like any other musical work previously heard because it came out of a mix of different genres and an original blend of high-cultured and popular features. After all, Bernstein, excellent pianist and conductor of the 'serious' Western repertoire, was one of the few in the XX century to give the word 'divulgation' the most positive possible meaning. Had there been more people like him in the world, maybe this research would not have many reasons to be (and, of course, I am referring to one of the less important effects).

Leonard Bernstein in 1956.

West Side Story's songs are quite complex and surely more demanding than Man of La Mancha's, which are basically four: Man of La Mancha, The Impossible Dream, Dulcinea, and Little Bird, Little Bird,but only the first tries out a short counterpoint between the protagonist's voice and his servant in the last repetition of the melody. This is likely the reason why there are many interpretations of The Impossible Dream but many less, as far as I know, of the Man of La Mancha. In any case, the text plays an important role in the success of a song. In fact, one can see that a pianist such as Liberace, in video recordings from several moments of his career, preferred to play the melody of The Impossible Dream and act its text 'against' the music, as Bertolt Brecht would have said. Let us read The Impossible Dream's lyrics:

To dream the impossible dream

To fight the unbeatable foe

To bear with unbearable sorrow

To run where the brave dare not go

To right the unrightable wrong

To be better far than you are

To try when your arms are too weary

To reach the unreachable star

This is my quest, to follow that star

No matter how hopeless, no matter how far

To be willing to give when there's no more to give

To be willing to die so that honor and justice may live

And I know if I'll only be true to this glorious quest

That my heart will lie peaceful and calm when I'm laid to my rest

And the world will be better for this

That one man, scorned and covered with scars,

Still strove with his last ounce of courage

To reach the unreachable star

It is a simple AABA form, but what intensity it can achieve if well-interpreted! Nonetheless, certain problems connected to lyric singing are evident in both musicals. Plácido Domingo is ever-present, but, of course, it could be worse. He has been a full-formed tenor, with a lot of experience, a perfect sense of the stage and a voice that, despite being a little bit nasal, is characterized by quite intense vibrations (I am not referring to vibrato). However, when compared with other pop singers or actors-singers, Domingo loses for two reasons: first, one cannot understand clearly what he is singing, whereas a pop singer and even more an actor-singer can articulate every word; second, a powerful voice is a double-edged sword because it must be rationed according to the specific needs. Thus, to use all its power, independently from the context, is a mistake that only amateurs and old people can blunder. In fact, it is a mistake that, not by chance, he spread to other retiring singers ever since he adhered to the Three Tenors group.

The Man of La Mancha, live in Madrid - I, Don Quixote,

Richard Kiley and Irving Jacobson (1973)

The Man of La Mancha, The impossible Dream,

Brian Stocke Mitchell (2003)

After all, it happens that an experienced singer (just because I do not want to call him ruthlessly an old singer)70 might feel that his voice at a certain age is fading out, thus, as soon as he can, he strives to keep away his fears and any possible critique. The result is that he utters some abnormal, overblown and unnaturally high pitches that lessen the atmosphere that has been built up to that point. Besides the ever-present Spanish tenor, not every pop singer gives an impressive interpretation. Being a victim of the jazz type that, according to Bernstein, is the 'slang' in music, Caterina Valente uses it even when it should not be there, for example in America and Io mi sento così bella (I Feel Pretty). Celine Dion does not do much better: she wraps Somewhere with jazzy variations that can undoubtedly remove any trace of sentimentalism, but also misrepresents the original intentions. In general these and many other singers seem to think more about their voice than about the meaning of the words they are singing. There are only two exceptions that tower over those who interpreted musical's songs off stage: Julie Andrews who, from Mary Poppins (1964) to Victor Victoria (1982), showed that she has no rivals in musical films and similar genres; and Judy Garland who, assisted by a quite measured Vic Damone in a medley from West Side Story, gives a delicate interpretation of the song. Over everyone else, though, there is Michael Ball — one of the best interpreters of the English version of Les Misérables — for his very bright and emotional interpretation of Maria.

70 If literally translated, the original text says: “In fact, it happens that an old singer (just because I do not want to call him a singer old)…”. This simple noun/adjective inversion generates in Italian a semantic difference that went lost in English. “An old singer” is a singer who sang for many years, but it might imply a sort of affective closeness between the singer and who calls him/her that way. “A singer old” is just an elderly singer and it might pitilessly imply that that singer is too old to keep singing [EN].

I cannot dwell longer upon all the versions of Somewhere I listened to. Instead, it is time to spend some words on Man of La Mancha. As I have already mentioned, the most sung tune off-stage is basically just one, The Impossible Dream. Besides Domingo (now with Julia Migenes), of whom enough has been said, many other lyric singers interpreted The Impossible Dream, for example: Brin Terfel, Rolando Villazón, a 'vintage' Samuel Ramey, Ruggero Raimondi, Carlos Sánchez and others. Terfel is as impressive and masterful in such operas as Nozze di Figaro and Tosca as he is distracted and flat in The Impossible Dream, no matter how passionately Edo de Waart conducts the Dutch Radio Filhamonisch Orkest. However, if one wants to feel the thrill of being irremediably horrified, he/she must listen to Tango de Roxanne that Terfel dedicated to Sting. Luckily, many may recall the spontaneous performance of José Feliciano, Richard Roxburgh and, especially, Jacek Koman interpreting that piece in a medley sang in the musical film Moulin Rouge! (dir. Baz Luhrmann, 2001). But let us keep going with the singers' overview: was there a competition to be won by the most kitsch tenor of the last ten years, Rolando Villazón would be certainly one the finalists. He possesses all the flaws that Domingo has, but much more in excess and with no excuses about his age (in fact Villazón was born in Mexico City in 1972). Instead, Ruggiero Raimondi is much more sensitive as well as the superb baritone Carlos Sánchez who is not interested in knocking down the audience with his vocal power. One of the most important bass-baritones of the last decades, Samuel Ramey (1942-), sang The Impossible Dream in 1991 in front of many colleagues of his at the 25th Anniversary of the Metropolitan Opera House at the Lincoln Center. Back then Ramey was 49 and was at the highest of his artistic maturity. He did not need to push his voice out or being schmaltzy in order to give a very beautiful 'mirror' interpretation. In other words, he interpreted himself, that is, the famous bass Samuel Ramey in the most known off-stage performance of The Impossible Dream. Unforgettable!

Halfway through lyric and pop singing — which is eventually the way taken by most of musical singers — there is the Spanish Paloma San Basilio with her interpretation of El sueño imposible full of energy en pathos. After all, these are the features of San Basilio when she engages in something dramatic, whereas she does not seem to be at ease with comedy songs.

The other side of a song's interpretation (jazz and pop) frequently holds many surprises. Above all in this specific case, the selection I made does not reflect the large amount of versions I listened to. I will just talk first about Luther Vandross and Aretha Franklin, and then about Matt Monro, Tom Jones and Frank Sinatra. Eventually I will get to Elvis Presely' many versions of the song. A separate case is Colm Wilkinson, the historic interpreter of many editions of Les Misérable, including the recent musical film where he, by now advanced in years, interprets the bishop Digne.

Valdross, instead, takes a jazz turn, but his blue notes seem over the top, as are those of Aretha Franklin. The cinema audience knows this icon of Rhythm&Blues, Soul and Gospel thanks to his cameo in the film The Blues Brother (John Landis, 1980) where he sings Think (the recording, though, goes back to 1968). In the live performance of The Impossible Dream, Aretha Franklin elaborates so much on the song's melody that she makes it unrecognizable. I think that one should evaluate a singer for how he/she interprets the inseparable bond of text and music. I also think that appreciating and even loving a singer just for his/her unique voice timbre and virtuosity is a misleading way of comprehending the art of music. In music, in fact, the voice and/or the instrument are the means a composer and an arranger use to achieve the same goal. As Aretha Franklin did with The Impossible Dream, similarly she made Somewhere from West Side Story an unrecognizable song.

Three unique voices take the opposite direction, that is, far from the above mentioned 'liberties', when they sing The Impossible Dream. They are Matt Monro, Tom Jones and Frank Sinatra. Monro had the beautiful voice everyone can recall from the song From Russia with Love, tune of the film by the same name (dir. Terence Young, 1963). He had also one of the clearest dictions of his times. By then, Albert Broccoli and Harry Saltzman, the producers of the successful series Agent 007, had finally understood that the title song must go on the title credits. Tom Jones as well took part in the main song of one film from the same series: Thunderball (dir. Terence Young, 1965). Both interpretations of The Impossible Dream are nice, but Monro's — referring here to a recording made in 1967 — is certainly better than Jones' in 1969. The reason is simple: Jones starts fine, but some acciaccaturas and, especially, portatos on which he indulges (they are due to a slow metronome in all of his performances of the song) makes his interpretation corny, as he typically delivers his slow songs. Sinatra sings the first stanza almost a cappella and stretches the gap among semi-phrases. Then, at the second refrain, the orchestra fades in and the rhythm turns more pressing and regular. Considering that this is a recording made in 1966, it must be noticed that, unlike other songs recorded in those years, The Impossible Dream is vocally and instrumentally much more sober than usual — only a small female choir. Of course, in this way Sinatra's voice and the song come off very well.

For those who placed Presley's performances in the category of rock masquerades and pitifully smiled at the imitators of the singer's haircut and garbs (as many one can see in Las Vegas) his versions of The Impossible Dream are undoubtedly a pleasant surprise. Presley's diction is also very clear, within the limit of his singing style where every semi-phrase gets quickly muffled. I was able to compare three different versions: the first, 1971, was surely a live performance; the second, one year later at the Madison Square Garden in New York, was also live (the arpeggiation is definitely slower and here Presley takes the liberty of emphatically inserting some high-pitch notes); and the third (1974) is very likely a studio recording. All three of them have a small ensemble with a piano arpeggiating throughout and a vocalizing mixed choir that joins in at the repetition of the melody and follows the overall crescendo. The last quatrain is peculiar because is sung an octave lower while the choir stops vocalizing and enters in imitation. The very last verse ("To reach the unreachable star") leads to a change in register and tonality while it repeats the same quatrain which, in the long, final rallentando, is supposed to work as a codetta, although the song has none. Unfortunately, also in these cases, a sort of 'falling-in-love' with one's own voice can be noticed which brings along barely coherent choices from point of view of content. I know that by saying thus I will now have against me an army of fans of this jazz and pop music icon

With regard to Colm Wilkinson, he is one of the few who interprets off-stage not only The Impossible Dream, but also Man of La Mancha. Now, before attempting a general appraisal in the Conclusions of this part, here is a new and more compromising confession: while listening to the vast majority of off-stage interpretations I often wondered, besides the profit, qui prodest?71

71 Latin expression from Seneca’s Medea, act III, verses 500 and 501. It means: “Who benefits?” [EN].

Now let us go chronologically through the main editions I referred to at the beginning of this chapter.

Leonard Bernstein with part of the cast

at the premiere of West Side Story (rehearsal, 1957).

The original production, in the Winter Gardner Theatre of Broadway,

was staged 732 times before going on tour.

Picture from West Side Story. No set design. Conductor Michael Tilson Thomas, 2013. Act One, Quintet ["Concertato"]: To Night (Tony, Maria, Anita, Riff, [Jack] and The Jets, Bernardo and The Sharks).

Notice the absence of a set design. However, some women wear clothes that are more suited to be used in a stage version of the musical. This observation will be helpful in Part IV.