Miceli, Sergio

(ed. and transl. by Marco Alunno)

3.0. Film Music Concerts. Between rite and myth

The rite I am referring to is the concert rite, that is: bringing film music to the ‘serious’ music hall. The myth, instead, is the myth of cinema with its directors, actors and actresses who have already passed away and whose acting skills and charm we miss.

It is now a well-known fact that one the first prestigious conductors who performed film music concerts after WWII was Arthur Fiedler (1994-1979). For half a century he conducted the Boston Pops Orchestra, a symphonic orchestra that specializes in popular and light music. His successor at the podium was John Williams. Fiedler’s arrangements were often effective and always able to highlight the virtuosity of his musicians. To conduct film music in the second half of the 1940s was somehow like studying and transcribing the result of the audiovisual analysis of that music. This was true at least until the 1990s. But between now and then there is a quite important difference: at that time, no one would read those analyses, whereas many would listen to Fiedler and his recordings. On the other hand, there has always been an immeasurable distance between ‘scientific’ and ‘artistic’ performances concerning the same subject. Thanks to the word ‘Pops’ in the name of his orchestra, Fiedler’s repertoire could range from the Eine kleine Nachtmusik K525 by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart to Dmitrij Tiomkin’s music for the film Duel in the Sun (dir. King Vidor and other, 1946), Broadway musicals and Beatles’ songs. Therefore, with regard to the Liverpool band, it was not Luciano Berio the one who elevated their songs to the rank of high culture (this is at least what a certain Italian-centric tradition believes), but rather Fiedler.

The protagonists of this kind of show are mainly Ennio Morricone (1928-) and John Williams (1932-), both very different from each other but, presumably, equal in talent and fame being the two film music composers who stand out from the other. Usually, the beginning of Morricone’s concert activity is considered to be the concert at the Arena di Verona (Sept. 2002).31 However, as early as 1987, he performed, with Duch Light-Orchestra Metropole, a film music concert in Antwerp “in front of an audience of 12.000 fans.” (CD Sabam T8710).32 Anyway, keeping to tradition, let us consider the first Verona concerto as the beginning of Morricone’s uninterrupted activity (suspended at the moment in 2014 for health issues) as a film music conductor. In the last thirteen years, instead of composing film music (except for requests from a few old friends), he mostly devoted himself to bringing his music all over the world. After his debut at the Arena di Verona, many important concerts came along. I can recall here at least two: the concert recorded in Rome on November 7, 9 and 10, 1988, for the Morricone’s 70th birthday, and the concert at the UN Headquarters in New York in February 2007.

31 DVD Ennio Morricone - Arena Concerto, Orchestra Roma Sinfonietta, 5 choirs conducted by Mauro Marchetti, Stefano Cucci (2), Mauro Bacherini, Claudio Micheli; soloists: Dulce Pontes (voice), Susanna Rigacci (soprano), Gilda Butta (piano). Dir. Giovanni Morricone, sound engineer Fabio Venturi, produced by Luigi Caiola, Euphonia - Warner Music Video 5050467-0076-2-8, 2003. Source: Archive S. M., Florence. In addition to the video documentation I must add the experience of a live performance at the Mandela Forum in Florence (May 16, 2015).

32 CD booklet Ennio Morricone live - Dutch Broadcast Light-Ochestra Metropole, conducted by Ennio Morricone. Vocals: Alide Maria Salvetta. SABAM T8710. Source: Archive S. M., Florence.

Among many composers who conducted their own music, the other name to mention is undoubtedly John Williams. Judging from the large amount of his scores available on the market - one for all: the Suite Adventures on Earth from E. T. The Extra Terrestrial (Steven Spielberg, 1982) — one can evince that William’s attitude is completely different from Morricone’s.33 Morricone is so ‘jealous’ of his music that he rarely and unwillingly gives it to other interpreters. As an exception: the cellist Yo-Yo Ma34 and, before him, the outstanding German components of Trilogy.35 First of all, though, there are ‘his’ soloists, the only ones for whom Morricone made arrangements of his film music themes: Gilda Butta (piano), Luca Pincini (cello) and Paolo Zampini (flute), all of them musicians of the Roma Sinfonietta Orchestra.

33 John Williams, Adventures on Earth. From the Universal Picture “E. T. (The Extra - Terrestrial)”, MCA music publishing 04490009 (Full Score), 1982. At page 2 Williams wrote: “The music was designed to accompany the bicycle chase near the end of the film and as the young cyclist reaches escape velocity, E. T.’s theme is heard as they fly ‘over the moon’. The more sentimental music that follows, accompanies the dialogues as E. T. bids farewell to his earthling friends. This is followed by timpani and brass fanfares as the orchestra brings the film to a close.” As a video recording, I used l’Extra-Terrestre, Collector’s Edition, 3 DVDs (released for the 20th anniversary of the film). DVDs no. 1 and 2 contain several documents and the live performance of the music under the screen. Amblin & Universal Pictures 907 025 2, 2002. Source: Archive S. M., Florence.

34 CD Yo-Yo Ma Plays Ennio Morricone, Roma Sinfonietta Orchestra conducted by Ennio Morricone, Gilda Butta, Piano, Engineer Fabio Venturi, Sony Classical BMG SK 93456, 2004. Source: Archive S. M., Florence.

35 Promotional VHS. Tristan Schulze (cello), Aleksey Lugudesman (violin), Daisy Jopling (violin), Triology plays Ennio Morricone. Regia Paul Landauer, Reverso RCA Victor 74321 548542, s.d. Source: Archive S. M., Florence.

Morricone’s themes have been played in many concert halls not only by Yo-Yo Ma with his energy and virtuosity or the German trio without viola36 but, and mainly, by the three Italian soloists. Their repertoire includes also some chamber music pieces by Morricone, e.g.: the Cadenza for flute and tape extracted from the first movement of the Secondo Concerto per flauto, violoncello e orchestra (1993), and the three movements of Riflessi for solo cello. As for piano pieces, there is a rich series of options because Morricone composed many pieces for this instrument, e.g.: Rag in frantumi and 5 studi per il Piano-Forte. Regrettably, due to Morricone’s decision, his film music is not available to everyone and this is very unfortunate because a score comes to life and revives every time someone else plays it. The only option in such a situation is to listen to an unauthorized arrangement. However, I discourage everyone to do so because Morricone is like Rota, although for different musical reasons: if you change a little detail the whole score changes.

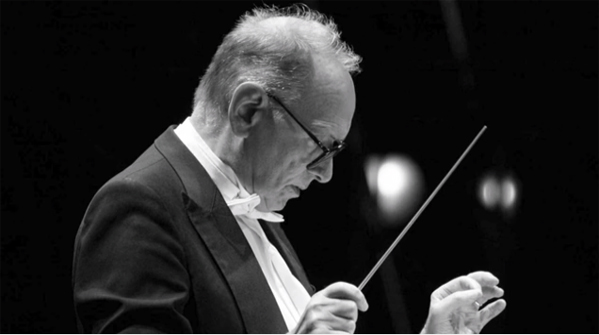

Morricone conducting (2012 approx.).

For reasons explained in the text (i.e. Morricone's ‘jealousy’ of his music) such bands as "The Spaghetti Western Orchestra" probably would not exist.

See YouTube, Live in London at the Royal Albert Hall 2011 (last accessed: end of 2013);

the same applies for the Norwegian Military Tattoo where the King Guard Band (2004) included in its repertoire two pieces that Morricone composed for Sergio Leone’s films.

See HMKG 04 Norwegian Military Tattoo, YouTube (last accessed: end of 2013).

36 CD Triology Plays Ennio Morricone, Reverso BMG RCA Victor 74321 548572, s.d. Archive S. M., Florence.

The concert activity of the two most important living film music composers is large enough to allow a partial evaluation of their work. In the Conclusions, though, I will also consider the production of other composers. Williams37 has the undeniable vantage of letting his scores circulate freely in the market. Of course, they might be tarnished by many amateurs, but they are also available to the best performers. For example, one can listen to The Imperial March from Star Wars episode V played by one of the best orchestras in the world: the Vienna Philharmonic conducted by Franz Welser-Möst.38 Unfortunately, after the last chord, two bass players started dueling with laser swords (a detail the broadcast direction could have omitted). Cheaper gags are sometimes set up by many other ‘minor’ orchestras that played this same piece. For example: when the Prague Film Orchestra (Pražský Filmový Orchestr) interpreted the Imperial March in 2010, the conductor George (Jiří) Korynta dressed up like the ‘dark side’ emperor. Fortunately, three years later in Bratislava, he decided to take off the costume. However, not everybody regrets these sketches. In fact, Bramwell Tovey conducted the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra first with a baton and then with a lightsaber. There is no need of more examples. Just remember that there have been many concerts where Darth Vader replaces the conductor, especially in Ukraine.39

37 On John Williams see Emilio Audissino, John William’s Film Music (Madison: The Univerity of Winscosin Press, 2014). Source: Archive S. M., Florence.

38 Performance realized during the Summer Night Concert 2010 at Schloss Schönbrunn (Schönbrunn Palace). Source: YouTube (last accessed Nov. 2014).

39 The examples cited in the text, from Prague to Ukraine, are all available on YouTube (last accessed Nov. 2014). Notice that the more the orchestra is widely known, the more its performance of film music accompanied by gags stands for: “We were kidding. We usually play a different kind of music.” That Williams’ film music is the most subjected to be performed with gags, is a matter I cannot explore here.

John Williams acquired an enviable conducting experience being the principal conductor of the Boston Pops Orchestra since 1980. As the successor of Arthur Fiddler in that position, Williams has conducted music of the most important composers between XVII and XIX century. Audissino wrote:

The Boston Pops post was the unique chance for Williams to advance further step in his effort to revive the classical Hollywood Music. From such a prestigious podium, he could contribute in creating a canon of Hollywood music and disseminate the best pieces in live concerts, radio and TV broadcast, and orchestral albums. Williams had the occasion to crack the “iron curtain” that had been keeping film music out of concert programs on the grounds of prejudicial points. Film music can be a source of legitimate music and an important repertoire from which symphonic pieces can be drawn for symphonic popular programs as those of the Boston Pops.40

40 Audissino, John Williams’s Film Music, 187.

As it can be evinced from the words of one of the sharpest scholars in Williams, even in North-America there are some prejudices against film music as a whole. And they cannot invoke any typically Italian mitigating circumstances as Italy can do by recalling that musicologists and composers have been dominated by the Crocian idealism.

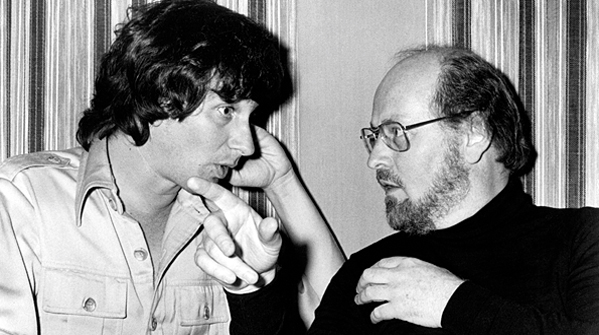

In the DVD collection released for the 20th anniversary of Steven Spielberg’s E. T. (1982), John Williams conducts a large orchestra in a live performance of the soundtrack during the film’s screening. Here he composer shows deep dedication and skill in an endeavor that would intimidate anyone. The result reveals that Williams is one of the most experienced and talented film and concert music composers of our time, one who thoroughly practiced music since childhood (his pianist skills are proof of this). The DVD collection also features many short bonus videos such as, for example, Spielberg and Williams preparing the soundtrack to E. T.

Williams and Spielberg in 1981, one year before the relase of E. T.

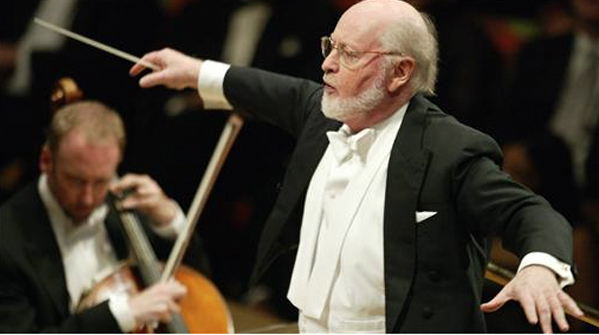

Williams in the 2002.

Comparing Williams and Morricone, there is much more seriousness in the Roma Sinfonietta Orchestra and Morricone himself, who is very far from appreciating the above mentioned gags (try to picture him conducting L’estasi dell’oro while wearing The Good’s poncho). Although Morricone’s conducting gesture is mechanical, ripetitive and most of the time unnatural,41 he is even too conscious that a concert is the place where his music can achieve a higher status, certainly higher than being ‘just’ film music. It actually makes of it an ‘absolute’ music (which proves again what I have been contending for years: what Morricone composed for film has always been somehow ‘absolute’ music).42 The humor, the sarcasm and the self-irony that Morricone was fully able to deliver in the music of, for example, Elio Petri’s films, completely lack in these concert venues. After all, Morricone conducting his film music was something unexpected when one considers that up to the mid-1980s he kept the two compositional activities (concert and film music) well apart. Thus, nowadays Morricone is not ashamed anymore of his work, so much so that he proudly presents it in a concert hall.

41 Every melomaniac knows that often the composer is not the best conductor of his/her music. The example of one of the biggest names of the past century suffices: Igor Stravinskij. As it is known, in order to listen to a good performance of Stravinskij, one should look for other conductors, starting with Ernest Ansermet onward.

42 This would be also a subject to deal with in another context. While waiting for a much hoped update of the book published more than 20 years ago and translated into Spanish and German (but, ironically not in English), see Sergio Miceli, Morricone, la musica, il cinema (Milan-Modena: Ricordi-Mucchi, 1986).

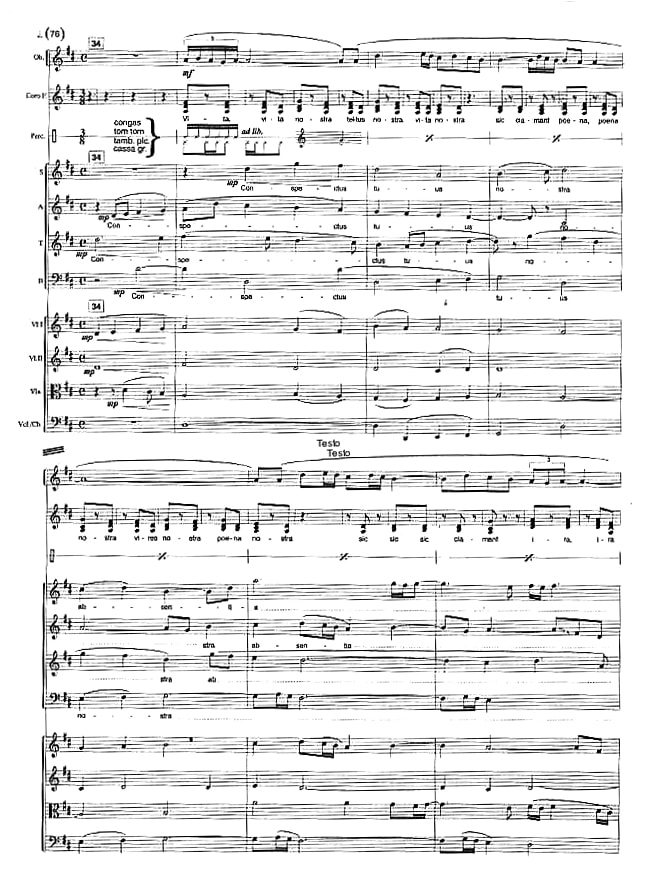

First page from the score of The Mission, Orchestral Suite.

(S. M.: transcribed from a recording).

The Mission by Roland Joffé, 1986. Orchestral Suite from Arena di Verona 2002.

From YouTube (last accessed 2012).

All this is very understandable except for a doubt that does not concern Morricone’s position toward his music, but rather what I previously said about a demi-cultivée audience. Indeed, it could concern every concert of film music as a whole. My doubt mainly refers to those who, after having approached some ‘educated’ symphonic music, have been then shocked while listening to a contemporary composition coming from Darmstadt and similar places. Said otherwise, I wonder whether the great, global, intergenerational and intercultural success Morricone had once in his intense film music career, now, in a concert hall, is not due also to a sort of compensation looked for — even unconsciously — by those who felt abandoned by the cultivated music of the XX century, starting with Schönberg’s expressionism.

Williams, instead, does not even seem to be touched by this train of thoughts. From his golden island — Hollywood — he conducts with no dilemmas whatsoever what he defines in a disparaging manner “little marches.” Williams seems more relaxed, maybe because he knows that in the end it is just a game (although a very sophisticated one), whereas Morricone has devoted a great deal — the last twenty years — of his professional activities and image in conducting film music.

Page n. 58 of "Adventures on Earth" from E. T. by Steven Spielberg, 1982.

Kind permission of MCA Music Publishing, 044900009, 1982.

Williams conducts "Adventures on Earth" from E. T. (1982 ca.).

Besides Morricone and Williams, many other composers brought their film music in the concert hall: Nino Rota, Trevor Jones, Franco Piersanti, Luis Bacalov, Alexandre Desplat, David Arnold, Paul Glass, Nicola Piovani etc. On the other hand, it is not very common that a film music composer plays the music of another film music composer. From this point of view, US composers are the most altruists or, at least, those who show a remarkable sense of corporatism. Specialized composers in film music are also helped by conductors who frequently devote their time to this kind of music: above all John Mauceri, David Newmann and Adriano, but also, although less frequently, Michael Tilson Thomas, Esa Pekka-Salonen, Riccardo Muti, etc. In addition to them, there are also scholars-conductors who apply philological methods to the reconstruction of the original music of important silent films, i.e.: the musician, musicologist and director Gillian B. Anderson, perhaps the best, Berndt Heller, and the film historian Enno Patalas.43 There is, finally, who accepts some risk and tries to be more ‘inventive’ with silent film music; for example Timothy Broch, who is often invited to Italy at the Giornate del Cinema Muto in Pordenone.

43 With regard to this aspect see the yearly festival “Il cinema ritrovato” that takes place in Bologna since 1986 and was created through an initiative of the Cineteca.

Among the most recent examples of film music played in a concert hall there is Giuseppe Grazioli conducting the Orchestra Sinfonica Verdi in Milan in 2014 for Robert Wiene’s film Der Rosenkavalier. The score was Richard Strauss’ original reduction for salonorchester on the screenplay Hugo von Hofmannsthal, author of the opera’s libretto, prepared for the film version.44 The simple fact that Strauss was not a film music specialist (in fact, this is the only work he composed for cinema) muffles the enthusiasm for Grazioli’s choice quite a lot. This can be explained when one thinks that between 1880 and 1980 the aesthetic attitude of most Italian musicians and musicologists toward film music was compromised by a neo-idealistic, very abstract stand that was totally uninterested in the audience’s opinions and reactions. At best, such a position led them to close the discussion after having watched one movie and read one book. Many misunderstandings originate thereafter: the only film considered was a copy, often in need of restoration, of Aleksàndr Nevskij (Александр Невский, by Sergej Ejzenštejn (Сергей Эйзенштейн), with music by Sergej Prokof’ev (Сергей Прокофьев), 1938); the only book was the 1969 re-edition of Komposition für den Film by Theodor W. Adorno and Hanns Eisler (but without the latter, who by then had passed away).45 Very few either knew the importance of Eisler in and out of cinema or bothered to question Adorno’s colossal absurdities about film and film music,46 but the book was highly praised anyway because of the German philosopher’s illustrious name. If Adorno’s sociology applied to film music caused damages that are still detectable nowadays above all in the United States (where even the most skilled scholars seems to feel a sort of uncritical subjection for the Marxist sociologist), Italian neo-idealism of the XX century had seriously heavy consequences for applied music and music in general. In fact, Italian specialism in composing film music began only at the end of the 1950s, right after Neorealism and very late with respect to such countries as the United States, the USSR, Great Britain, Japan and pre-Nazi Germany.47

44 The reader should listen to what, I think, it is one of the few available recordings: Richard Strauss, Der Rosenkavalier, Begleitmusik für den gleichnamigen Film (Salonorchester-Fassung), conductor Manfred Reichert, Baden-Baden Ensemble 13 [11 musicians], 2 LPs (Folge1/2), LC 0761/2, EMI Electrola, Köln 1980. Although it is very hard to find, it is mandatory to mention also: Richard Strauss, Der Rosenkavalier, Begleitmusik für den gleichnamigen Film (Salonorchester-Fassung), conductor Richard Strauss, Augmented Tivoli Orchestra (Tivoli Cinema, Strand in London, 1926). This is a version of the salonorchester reduction rearranged for a bigger ensemble: 7 78rpm records, recording by Michael Dutton, Queen’s Hall, London 04/13/1926. Remastered in CD, Dutton, CDBP 9785, 2008. Source: Archive S. M., Florence.

45 Theodor W. Adorno and Hanns Eisler, Komposition für den Film (München: Rogner & Bernrhard, 1969), with an annotation by Adorno. I think that the only Italian translation that is faithful to the original is: id., La musica per film, intr. Massimo Mila (Rome: Newton Compton, 1975). For more information on the complicated publication history of this book see Mila’s introduction and the paper by Sergio Miceli, “Da Kurt London (1936), a Theodor W. Adorno (1947): due miti da ridimensionare,” in proceedings of II Giornata di Studi ‘La storiografia musicale e la musica per film,” ed. Roberto Calabretto (Venice: Fondazione Ugo & Olga Levi, 2012), forthcoming.

46 If this expression sounds exaggerated and disrespectful one can look for the support of more authoritative assessments; for example, one can read what bad opinion Brecht had of Adorno in Hanns Eisler, Con Brecht, interview by Hans Bunge, It. trans. Luca Lombardi, (Rome: Editori Riuniti, 1978), pp. 40-42. Source: Archive S. M., Florence. To know other ‘absurdities’ from the German philosopher see Theodor W. Adorno, Sulla Popular Music, It. trans. and ed. M.Santoro (Rome: Armando 2005).

47 For more information see Sergio Miceli, Film Music, 219-304.

Among the different ways of organizing a film music concert, there is the booming trend of reinterpreting famous silent films in a contemporary style in part by soloists and, more rarely, by ensembles.48 It would take too long to list them here; therefore I will mention only one that towers above the others: the Gruppo Live Electronics Edison Studio formed of four composers (Mauro Cardi, Luigi Ceccarelli, Fabio Cifariello Ciardi and Alessandro Cipriani).49 The high quality of their output in musicalizing silent films is partially due to the fact that they also work in other compositional fields.

48 For a general survey see Sergio Miceli, “Recuperi, Restauri e post-sonorizzazioni,” in Musica e cinema nella cultura, 241 ff.

49 See Edison Studio. Il silent film e l'elettronica in relazione intermediale, ed. Marco Maria Gazzano (Rome: Ėxòrma, 2014). The book contains articles by Guido Barbieri, Roberto Calabretto, Michele Canosa, Alessandro Cipriani, Flavio De Bernardinis, Edison Studio, Marco Maria Gazzano, Giovanni Guanti, Giulio Latini, Sergio Miceli, Quirino Principe, Marco Russo and Klaus Schöning.

With regard to the acceptance of film music in the world of concert music, interpreters are usually more open minded than theorists and musicologists. However, at least since the last decade of the XX century, such an open-mindedness could also be the result of an unscrupulous and unbiased attitude that is no longer rare to see in our time. But it has not always been like this and my memory still keeps quite an unpleasant recollection of it. It was back in 1983 when Luciano Alberti, at that time artistic director of the Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, asked me to propose some ideas for a thematic program on music in cinema. My cautious and well-accepted proposal came down to the Symphonic Suite op. 18 that the young Šostakovič (Шостакович) derived from the music50 for the silent film The New Babylon (Новый Вавилон) directed by Grigorij Kozinčev (Григорий Козинцев) and Leonid Trauberg (Леонид Трауберг) in 1929. Although the music was composed by a true Šostakovič and matched the style of other compositions of the same period like The Age of Gold, op. 22a, 1929-32 (Золотой век) and the Suite The Bolt, op. 27a, 1933 (Болт), many musicians of the Florentine orchestra refused to play it because they did not want to compromise their dignity.

50 Produced by Leningrd Sovkino Film Studio. First showing: 18 March, 1929. Score missing: a suite was restored from orchestral parts in 1976 by Gennadi Rozhdenstvensij. For more information see Sergio Miceli, Film Music, 49-52.

It is also true, though, that some of us, a few years earlier, had read and reflected on Umberto Eco’s Apocalittici e integrati.51 In that book, Eco made an example of Kitsch by referring to some film music (but not only that) performed in a concert venue.52

51 A partial translation of Eco’s book is Apocalypse Postponed, ed. Robert Lumley (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994) [EN].

52 Umberto Eco, Apocalittici e integrati (Milan: Bompiani, 1965), 130-131. Source: Archive S. M., Florence.

A typical example of musical kitsch is Addinsel’s Warsaw Concert with its accumulation of pathetical effects and imitative suggestions (“do you hear it? These are the airplanes bombing…”) that use Chopinian style in large amounts. A typical example of kitsch listening of this piece instead is what Malaparte describes in La pelle.53 He tells about a meeting of English officials. During the meeting they hear the sound of Addinsel’s music that the author initially confuses with Chopin. Then he realizes that it is a fake and adulterated Chopin and, eventually, one of the officials says with a basked tone: “Addinsel is our Chopin.” From this point of view, most of the so-called rhythmic-symphonic music sounds like Addinsel’s because it attempts to mix the pleasantness of dance music, the boldness of jazz and the dignity of classical symphonic style. [ET]

53 Curzio Malaparte (pen name of Kurt Erich Suckert, Prato (Florence) 1898 - Rome 1957), La pelle (Milan: Mondadori, 1978). The first edition was published in 1949. Source: Archive S. M., Florence.

I will come back on this important point in the Conclusions to Part I.

Concerts entirely dedicated to film music have exponentially increased in the last years. Just to make an example: the music of Lord of the Rings, performed by bands and small provincial ensembles or used even as didactic material in several junior high schools, is something with which the composer of the score, Howard Shore, has little to do.

James Horner, instead, has much to do with a curious circumstance that I will mention here and I will not comment further on: on a different scale from the provincial performances, successful film music is frequently played all around the world, e.g.: Hollywood a Vienna 2013, a concert of the Wiener Konzerhouse with the ORF Radio Symphonie Orchester Wien conducted by David Newman. In this kind of show music by different composers is usually performed and images from related films are often screened, perhaps in order to exorcize a ‘stone guest’ atmosphere that some concerts reluctantly offer to their audience.54 However, in Hollywood a Vienna 2013 all the music played (from Star Trek, Gattaca, Braveheart, Avatar, Titanic and so on) is by James Horner, but the Gala program does not say it explicitly. This might be understandable because that concert was performed to award Horner with the Max Steiner prize that every year is granted to a distinguished film music composer. Horner certainly deserved it, but why not say it clearly?

54 The allusion refers to a certain kind of film music where the absence of images yields a sort of expectation similar to the uneasiness one can feel in the last scene of Molière’s Don Giovanni.

Before closing this chapter, I will mention some of the ‘altruist’ musicians who performed film music: David Raksin, who conducted his and other music, the Moscow Soloists conducted by no less than Yuri Bashmet (Юрий Башмет), and Michael Nyman with his Band. A roughly complete list would take the space of a long essay, therefore the few examples above are just a small part of the whole group.

Original VHSs and TV video recordings, LP, cassettes (mostly from the Archive E. M., Rome), home-recorded 1/4-inch tapes, films in DVD and multimedia CD, musical CDs (from the Archive E. M., Rome), downloaded movies and soundtracks, several55 video clips of Ennio Morricone and John Williams.

55 Part II will replace this generic adjective with something more specific when referring to a specific example. Here, I had to be concise, due to the large quantity of examples coming from numerous sources.

Ennio Morricone conducting the Roma Sinfonietta Orchestra, the Arena di Verona Choir, Video Director Giovanni Morricone, (28.09.2002), Soloists: Dulce Pontes (voice), Suanna Rigacci (soprano), Gilda Buttà (piano). DVD Euphonia 2013, Warner Music Vision, Pal 16:9, All Regions, Dolby Surround 5+1, Dolby Digital 2.0, language: Italian, dialogues subtitles: English. With extras. No other available data.

Archive S. M., Florence.

John Williams conducting a live performance of E. T.’s soundtrack.

Italian release 3 DVDs Amblin - Universal Pictures 907 025 2 (2002). The soundtrack is digitally remastered [i.e., it is not the original version conducted by Williams for the 20th anniversary]; there are also some computer graphics’ image editing.

- Disc 1: Introduction by Steven Spielberg; Feature Film (20th Anniversary edition); John Williams at the Shrine; Auditorium 2002 Premiere.

- Disc 2: Evolution and creation of E. T.; The reunion; The music of John Williams; The 20th Anniversary Premiere; Space Exploration; Designs, Photographs and Marketing; Trailer; DVD-ROM Features Including Total Axess [only for Microsoft Windows].

- Disco 3: E. T., the Original Film; A Look Back; The Original Trailer; DVD-ROM Features Including Total Axess [only for Microsoft Windows].

Available subtitles: Italian, English, Croatian, Serbian, Slovenian. Content Audio: Italian-5.1-EX; Italian-5.1-dts-ES; English 5.1-EX; Polish 5,1 EX (only disc 3). Anamorphic Widescreen 1.85:1, PAL 2.

CD John Williams, E. T. The Extra Terrestrial, The 20° Anniversary, 21 tracks, 1982, Music Composed and Orchestrated by John Williams, online version, Apple iTunes. No other available data.

Archive S. M., Florence.

John Williams, Adventures on Earth. Full Score from the Universal Picture “E. T. The Extra Terrestrial”, New York: MCA Music Publishing [Geffen Records] 04490009, 1982/2002.

Ennio Morricone, Concerto alle Nazioni Unite, New York, February 2, 2007, Video Director Giovanni Morricone, PAL 4:3, All Regions, PCM Stereo DTS, Dolby Digital 5.1 DVD Ars latina. No other available data.

Archive S. M., Florence.

Many other symphonic and choral ensembles in previously, live concerts in different locations.